by Lauren Davis

Parliamentary procedure is underpinned by the understanding that each delegate involved in a negotiation knows exactly what text is under discussion at any given point. Presumably, delegates would be aware of the effect each proposed amendment would have on the text as it existed at that day and time. This understanding, however, is largely lost to us as readers. We can read accounts of these amendments to the text in official journals, but the minuted record almost entirely divorces the drafting of these documents from the important context in which the decisions were made.

Seeking to shed new light on the complex drafting process surrounding the Constitution of India, PACT utilises the bespoke software of the Quill Project (Pembroke College, Oxford), which combines traditional archival research and innovative digital methods, to reconstruct the context surrounding the drafting of this foundational document.

Quill foregrounds the story of the archive: how meaning is created and enacted on the word level. What was the text before an assembly when certain amendments were made or speeches given? It places the archive in context, allowing users to track the contributions of individuals, the evolution of certain phrases, and the paths a negotiated text, such as a constitution, took throughout various committees, for example.

But on an even more basic level, it brings together disparate source materials, many of which have been previously unavailable for public consumption. Any Quill project begins with a survey of available source materials. For the Constitution of India project, the logical place to begin was with the Constituent Assembly Debates, a verbatim record of the Constituent Assembly proceedings. This verbatim record can then be parsed into one of four overarching ‘event’ types – person events, document events, procedural events, and decision events – which are represented as icons in a digital model. These broad categories can be further subdivided to capture the nuances of the event. The result is an interactive timeline that users can click through to see how the constitutional text changes amendment by amendment, day by day.

This methodology has already revealed several interesting findings, one of which is the unique role of the Constitutional Adviser, an appointed official to the Assembly that has no parallel in the other constitutional conventions digitised by Quill, such as United States federal and state constitutional conventions or the Australasian federation conferences and constitutional conventions. The closest office from these conventions and conferences is the Secretary, but like the Secretary of the Indian Constituent Assembly, the secretaries of these conventions were not authorised to create constitutional text.

The responsibilities of the Constitutional Adviser included things like circulating a questionnaire on constituting the Union, drafting memoranda on provincial and union constitutions (upon which those committees based their discussions and subsequent reports to the Constituent Assembly), and presenting a constitutional draft. He was not, however, elected to represent a constituency like the delegates were. In other constitutional conventions, such as those mentioned above, this fact would preclude him from creating constitutional text and serving on committees.

However, the archive reveals that he did just that. A comparison of archive documents reveals how much power he had to make decisions to the text that, based on the available record, do not appear to have been the product of negotiation. The following example takes the 1947 sessions as scope, as they represent a period of textual – rather than theoretical – negotiation, but predate a long constitutional draft and the complicated negotiation that accompanies one.

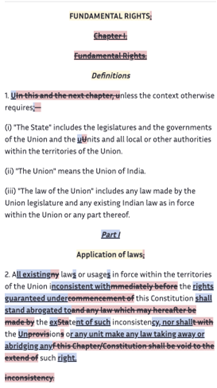

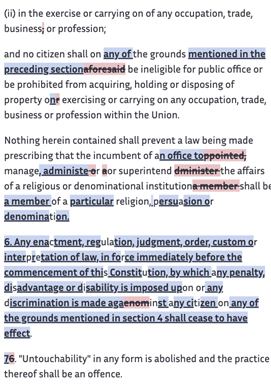

In the Advisory Subcommittee on Fundamental Rights, the committee took up a draft on the subject introduced by K.M. Munshi. As is typical parliamentary procedure, the committee severally considered the clauses, amending and voting on each one. From this clause-by-clause treatment of the document resulted an amended version of the text, shown in the left-hand images below, that was to be reported to the Constituent Assembly.

Modelling this process in the Quill software reveals, however, that this text is not what was reported to the Constituent Assembly. Rather, a heavily amended version of the text agreed by the committee, shown in the right-hand images, is reported. In these images, red text represents deleted text, and blue represents inserted text. These changes are both superficial drafting amendments and substantive changes, changes that – based on several documented instances of his revision of clauses – were presumably made by B.N. Rau and not concurred in by the committee. In other words, it is possible that an official who was not elected to represent a constituency could make substantive, unilateral changes to the text under consideration. This then becomes a hypothesis for testing through further archival research.

This example is one of several that demonstrates the value of applying a digital humanities approach to the study of documents that have been the subject of much traditional academic research. By foregrounding the story of the archive, much of which has been buried in boxes and untouched files, and reconstructing on a digital platform the context within which this foundational document was negotiated and written, we acquire better knowledge of processes of constitution-making.

The Quill model of the Constitution of India negotiations is a work in progress and will be made public as part of the PACT Exhibition in 2025.