by Manas Raturi

In recent years, the Indian Constitution has become both a site of contestation between various political parties and a symbol of civil resistance against the state. Prior to 2019, the Indian Constitution remained relatively obscure in public discourse, despite shaping everyday life in fundamental ways. However, the widespread public protests against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 brought the Indian Constitution to the forefront of public and media conversations.[1] For Arvind Elangovan, these developments highlight the significance of the Indian constitution in its political articulation – a process which invites an understanding of the text that extends beyond a purely legal and normative interpretation.

A recent development in this process of political articulation is the museumisation of the Indian constitution. Lately, we have seen a proliferation of several exhibitions, galleries and museums that have come up to showcase the Indian constitution as a cultural artifact of national heritage. Several initiatives illustrate this trend. In August 2021, the Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, as part of the ‘Azadi Ka Amrit Mahotsav’ programme, launched a series of e-photo exhibitions, including one on the making of the Indian Constitution. In 2022, the new Pradhanmantri Sangrahalaya was opened to the public as part of the newly reconstituted Prime Ministers’ Museum and Library (PMML, earlier the Nehru Memorial Museum & Library, the NMML) with its ground floor reserved for a ‘Constitution Gallery.’ In November 2024, a Constitution Museum was inaugurated at the O.P. Jindal Global University by the Union Law Minister and Lok Sabha Speaker. Recently, a ‘Constitution Gallery’ was inaugurated at the Maha Kumbh mela – one of the most significant Hindu pilgrimage festivals – by the Uttar Pradesh government’s Parliamentary Affairs Minister.

The display of the Indian Constitution in curated spaces raises important questions. In the context of representation of tribals in post-colonial India, Neela Karnik reminded us that museums also shape “knowledge by constructing material things as objects and ordering these in taxonomies – of the ‘rational’ or the ‘truthful’.”[2] One might then ask: what frameworks does the state deploy in the exhibition of the Indian constitution in dedicated sites of public display?

A visit to the Constitution Gallery in the PMML serves as a good starting point. The gallery is situated in the historic Teen Murti Bhawan in Lutyens’ Delhi. Designed by British architect Robert Tor Russell, the Teen Murti Bhawan was originally built in 1930 as the Flagstaff House for the Commander-in-Chief of the British forces in South Asia and later became the residence of India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru. After Nehru’s death in 1964, the complex was converted into a library and a museum – the NMML. In 2018, the government announced its plan to reconstitute it into the Prime Minister’s M…L and to expand its focus beyond Nehru to incorporate the legacy of all former Prime Ministers. When the new museum was opened up, it contained a ‘Constitution Gallery’ dedicated to the making of the Indian constitution.

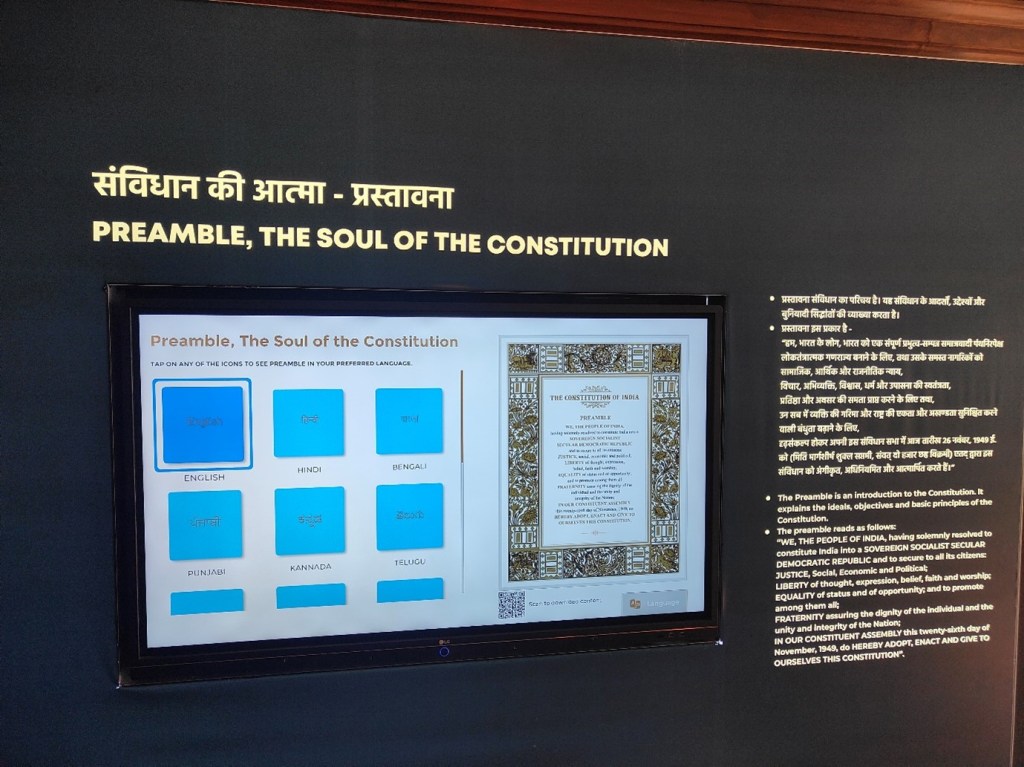

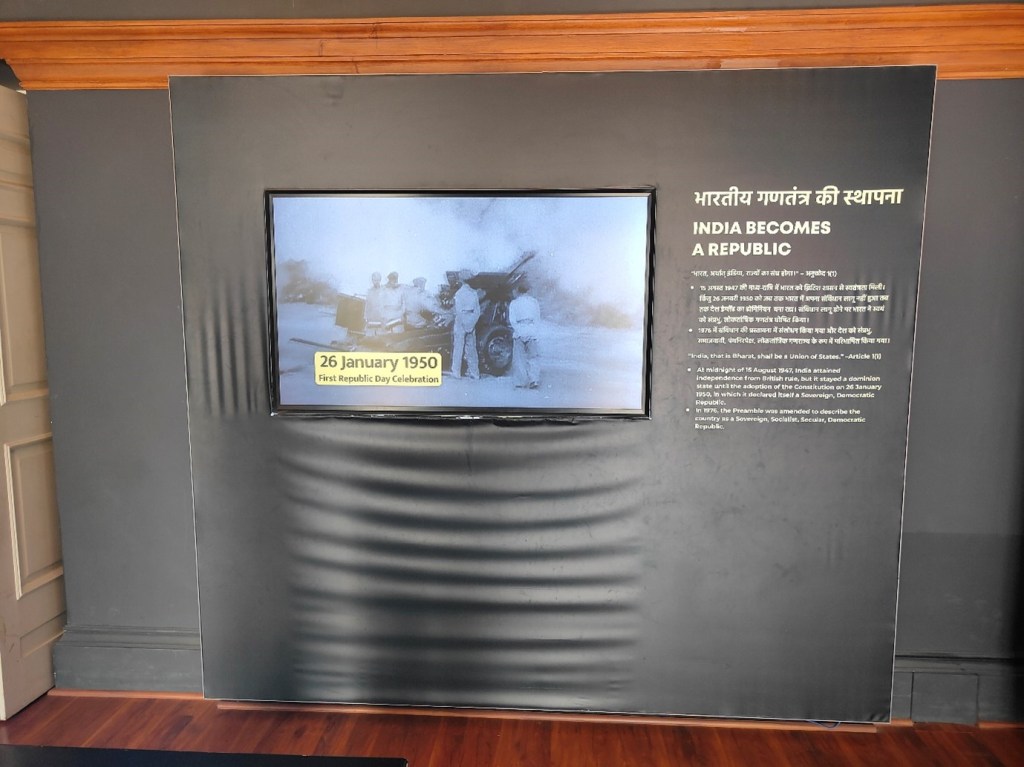

In its own words, the gallery intends to offer an ‘experiential’ view of the Indian constitution. Spread across different rooms, the gallery contains exhibits showcasing the Preamble of the Indian Constitution in multiple languages, alongside pictures and videos from the first Republic Day parade on 26 January 1950.

The Preamble in multiple languages (Source: clicked by author at the PMML)

Footage from the first Republic Day celebrations (Source: clicked by author at the PMML)

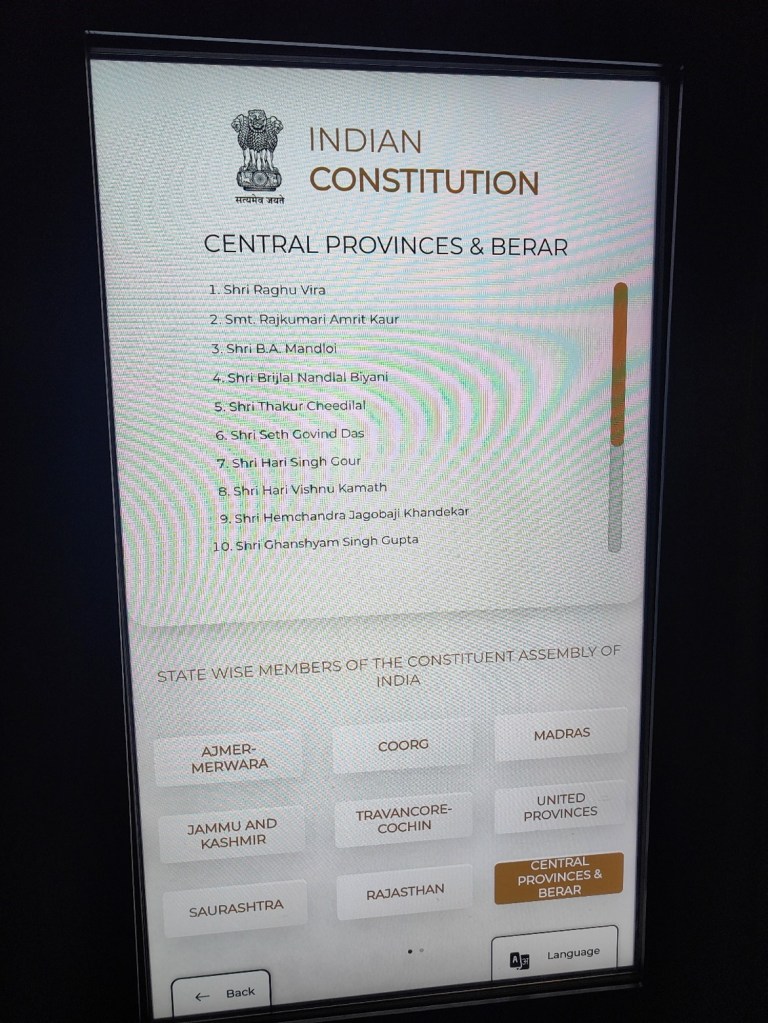

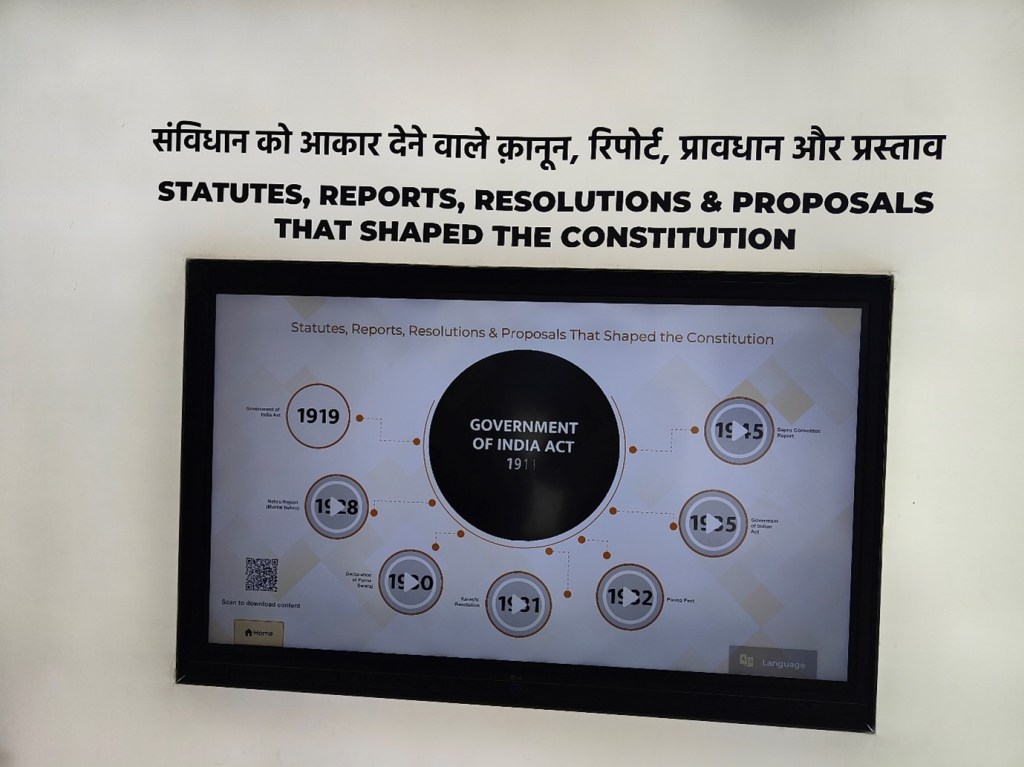

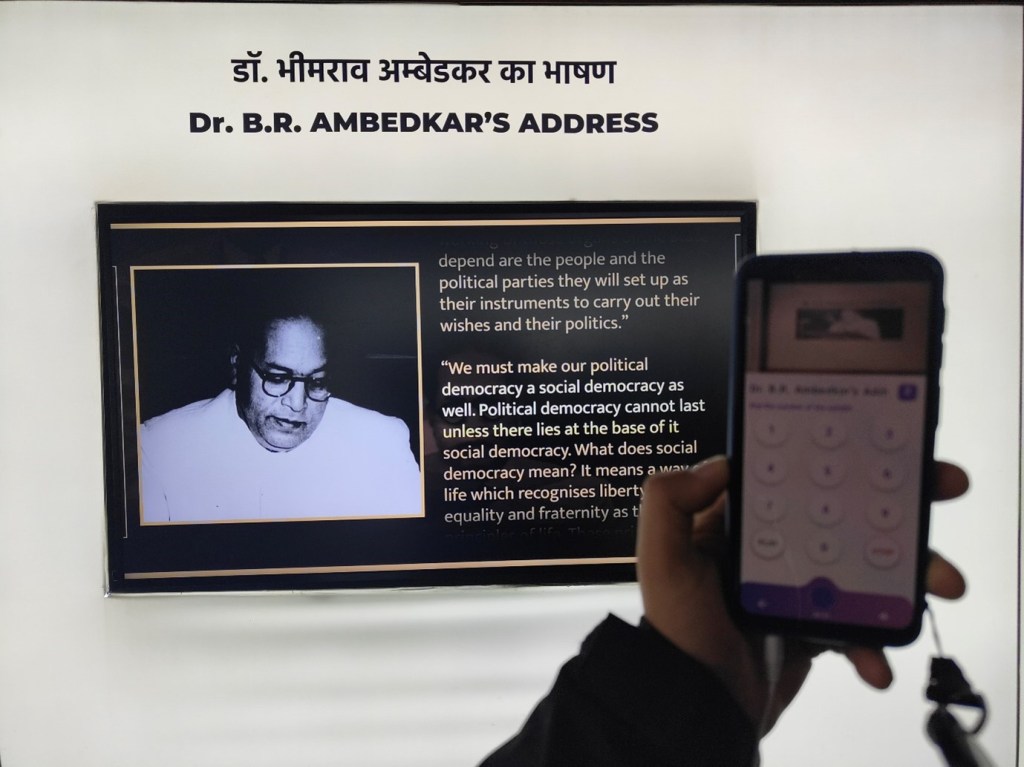

Visitors can view a digital display with the first edition of the Indian Constitution and explore its key features, such as the separation of powers or directive principles of state policy. Interactive screens provide a comprehensive list of Constituent Assembly members, their constituencies, and the various committees and subcommittees. A detailed timeline traces the significant statutes, reports, resolutions, and proposals that led to the formation of the Constituent Assembly, beginning with the Government of India Act of 1919 and to the 1945 Sapru Committee Report. It also highlights pivotal moments, such as Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s address to the Constituent Assembly on 25 November 1949 and the first general elections in 1951. Additionally, a dedicated room focuses on the 105 amendments to the Indian Constitution up to 2021. These displays are accompanied with a physical audio guide the visitor can get to hear audio recordings playing in each of the rooms.

Details about the first edition of the Indian Constitution (Source: clicked by author at the PMML)

List of members of the Constituent Assembly of India and the constituencies they were elected from (Source: clicked by author at the PMML)

Details of different legislative reforms, reports and proposals that culminated into the making of the Constituent Assembly of India (Source: clicked by author at the PMML)

A room dedicated to some of the most significant constitutional amendments (Source: clicked by author at the PMML)

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s last speech in the Constituent Assembly of India and the audio guide (Source: clicked by author at the PMML)

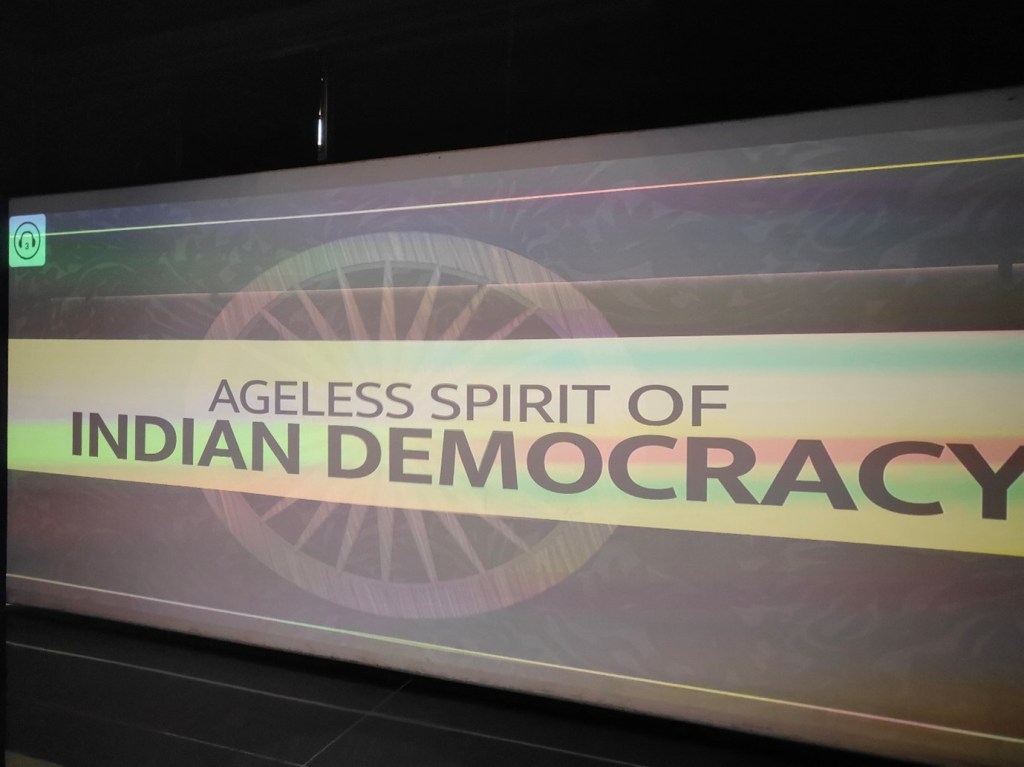

What merits attention are the different films being played in these rooms through which the Indian Constitution is portrayed as direct result of a seemingly continuous political tradition of democracy in India. The colonial rule is portrayed as a major disruption in an otherwise seamless history of democratic governance in the Indian subcontinent. Before the colonial presence, the pillars of democracy were firmly entrenched in this part of the world, the gallery tells us. In a room dedicated to ‘Makers of the Indian Constitution,’ for instance, a film shows a montage of images and videos to highlight the ‘ageless spirit of Indian democracy.’ The idea is to underline India as a historical site for deliberative assembly and popular participation through highlighting references from the Rig Veda and the presence of gana sanghas like that of the Shakyas and Licchavis.

A film that showcases how the roots of democracy were firmly entrenched in ancient India (Source: clicked by author at the PMML)

Whether these governing bodies and councils were indeed democratic or more aristocratic and oligarchic has been a point of scrutiny in scholarship.[3] Nevertheless, the description of Indian democracy as a historically continuous trend aligns neatly with the current representations of India in government discourse as a ‘mother of democracy’.[4] Through its ‘experiential’ setup, the gallery tells us that prior to colonial rule, the Indian subcontinent saw a flourishing tradition of freedom of religion, culture, art, linguistics and diverse belief systems. By framing the story of the Indian Constitution thus, the gallery links modern constitutional ideals with an ancient tradition of democracy in India. It suggests to visitors that the foundational principles of the Indian Constitution were deeply rooted in India’s ancient history.

It is important to remember that the Indian constitution emerged not only from a struggle against foreign colonial rule, but also from a confrontation with an internal feudal social order. The final text was far from a harmonious culmination representing continuity with ancient traditions. Rather it was the outcome of a series of contesting social struggles and political negotiations among widely contrasting groups – both within and outside the Constituent Assembly – regarding the future of the Indian society as a modern polity. In the process of its museumisation and elevation into a cultural artefact, we need to recall the Indian Constitution’s complicated history of a struggle against both external colonial forces and internal systems of oppression.

When the PMML was reopened in 2022, it garnered much debate on the possible revisionist tendencies to dilute the legacy of Nehru. But what perhaps deserves greater attention is this political articulation of the Indian Constitution through a narrative of seamless continuity between ancient democratic traditions and modern constitutional ideals. The Indian Constitution may not best be served by being portrayed as the inheritor of an unbroken civilisational legacy with its authority rooted in a mythologised past.

[1] Arvind Elangovan, ‘A political turn? New developments in Indian constitutional histories,’ in History Compass, Vol. 20, no. 8 (2022), e12746 [https://doi.org/10.1111/hic3.12746].

[2] Neela Karnik, ‘Museumising the tribal: Why tribe‐things make me cry,’ in South Asia, Vol. 21, no. 1 (1998), 275-288 [https://doi.org/10.1080/00856409808723337].

[3] See Romila Thapar, Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300 (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2004), p. 147 and Eric W. Robinson, The First Democracies: Early Popular Government Outside Athens (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1997), p. 23.

[4] See Suhasini Haidar, ‘India is indeed the mother of democracy, says PM Modi citing Mahabharata and Vedas,’ The Hindu (29 Mar. 2023) [https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/india-mother-of-democracy-home-to-idea-of-elected-leaders-much-before-rest-of-world-pm-modi/article66675267.ece]