By Arvind Kumar

The Indian Constitution has completed 76 years of existence in 2025. It is an appropriate time to reflect and ask ourselves to what extent has the Constitution reached the Indian masses?

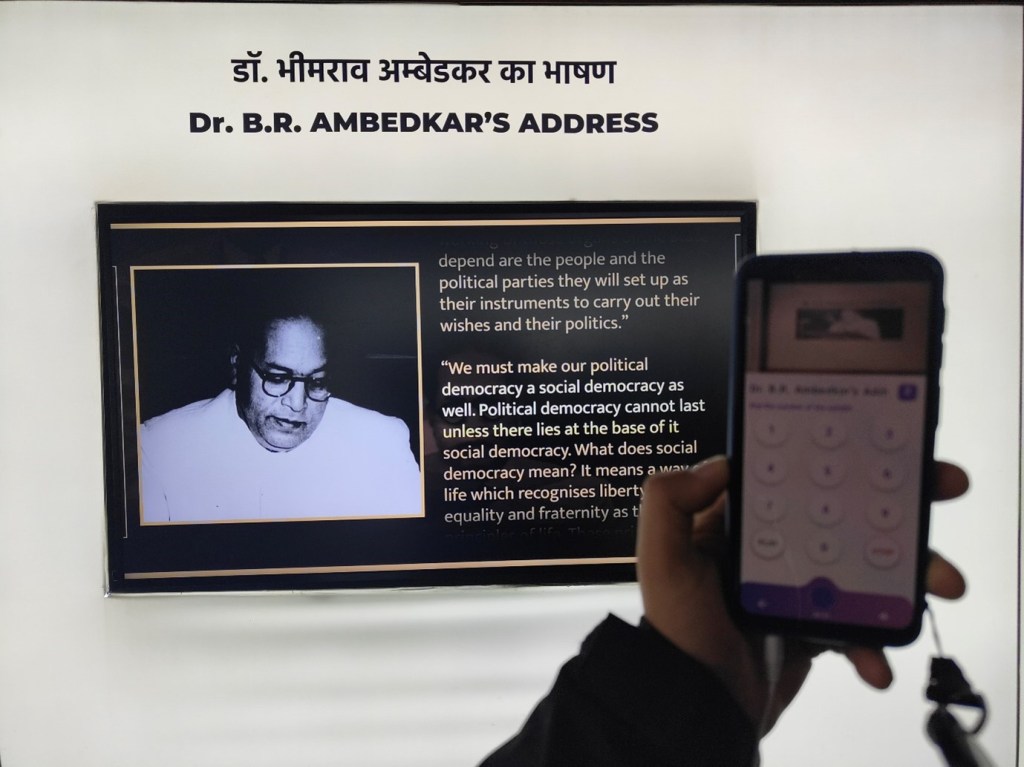

My own recollections and impressions developed in the course of my research and education in rural Uttar Pradesh suggest that the constitution has mass reach is viewed as a liberator from social and economic oppression by the marginalized. The installation of Dr. B. R. Ambedkar’s statues on public land in remote rural areas has given added visual presence to the constitution. The digitization of the constitution and the Constituent Assembly Debates has brought about a paradigm shift in rediscovering its meanings among scholars and citizens. The recent efforts of grassroots rights organizations such as the Jashn-e-Samvidhan yatras led by Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS) activists in rural Rajasthan provide a model for increasing constitutional awareness among non-English-speaking rural populations in deprived areas.

Discovering the historical memory of the Indian Constitution in my rural village

In the winter of 2016, upon my return to my rural village in eastern Uttar Pradesh from Delhi, where I worked as a university lecturer (Satyawati College, University of Delhi), I was asked an interesting question about the constitution by the oldest man of my village. He asked, ‘What is the first line of the Indian Constitution?’ The person’s name was Ram Samujh. He had not only passed the 8th standard in the 1950s, a rare achievement in the village, but was also the topper in the whole block(an administrative unit for rural development comprising around a hundred villages). He thus enjoyed the highest respect in my village. His question struck me deeply, and instead of responding directly, I enquired why he was asking this question. He replied that he had been informed that I had become a professor of political science at the University of Delhi, to teach the Indian Constitution. Upon further asking, he told me that during the 1960s, when the villagers of Tikari and Jaitpur picked up the fight against the practice of bondage labour (begari pratha), sitting on a hunger strike in front of the UP Legislative Assembly (Vidhan Sabha) against the local landlord, who was also their local MLA, they had been told that the first line of the Indian constitution says that bondage labour is abolished [Samvidhan Ki Pahali Hi Line Me Likha Hai Ki Begari Samapt Kar Di Gayi Hai].

In the hierarchy-driven Indian society, what is written in the first line of the Constitution, a prestigious document, matters quite a lot for ordinary people. In the 1960s, very few if any of the village residents had read the constitution, or even seen it, yet the knowledge of the line abolishing bondage labour (begari pratha) had inspired them in their travel to the capital city Lucknow and their hunger strike in front of the UP Legislative Assembly (Vidhan Sabha) against their powerful local landlord of Tighara estate (currently located in the Jalalpur Tehsil of Amebedkar Nagar District, Uttar Pradesh). The landlord, Jagdamba Prasad, had won the Jalalpur assembly constituency in the 1967 Uttar Pradesh Assembly Election as an independent candidate and in the 1969 Assembly Election as the Congress party candidate. The strike, in turn, led to the institution of a magisterial inquiry that eventually freed them from the practice of bonded labour, a traditional system of forced or compulsory labour without payment, a type of slavery. In the eastern and Awadh regions of Uttar Pradesh, workers from Dalit and Backward castes, such as Chamar, Nishad, and Pasi, were exploited through begari pratha. The Indian Constitution prohibited begar and other similar forms of forced labour under Article 23, but the practice had continued. The end of this exploitative system allowed members of these castes and communities freedom to choose their occupation and exercise their voting rights.

The question from my village elder had placed me in a dilemma: should I tell him the truth, after such a long time had passed since the event? I realised that my truth might harm him psychologically, as he might come to believe he had been fooled. Therefore, adopting a middle path, I told him that you are right that the constitution abolishes bonded labour, but instead of the first line, it is written on the first page of the constitution.,the Preamble of the Constitution which embodies the fundamental values of equality, liberty and social justice

Recollecting the social memory of the Constitution in Ambedkar statues and Awadhi Songs

My childhood memory goes back to 1993-94, and the announcement of the death of former president Gyani Jail Singh. During those days, Dalits in Awadh and Eastern Uttar Pradesh had started installing the statue of Dr. B. R. Ambedkar on public lands. They had evolved this strategy to counter the attempt of the upper castes to forcibly capture public lands by installing statues of gods and goddesses. The installation of Ambedkar’s statues with the constitution in his one hand forced the people to see the constitution. Not so different from Rousseau’smaxim that , ‘People should be forced to be free’, we could say Dalits forced people to see the constitution as the condition of their freedom. This might be one of the reasons why Ambedkar statues are so often desecrated.

The Constitution also lived in the memory of the rural masses in their folk songs. I can recall an incident of 1995 when the upper castes objected to a Bhimwadi song (Song on Ambedkar), which culminated in a near clash. The song praised Ambedkar for making the constitution, which had liberated the untouchables. It was titled ‘Baba Ho Samvidhanva Banaya Gaye, Jawan Achhutva Bhuiyan Bath Naa Pavain, Wahin Achhutavai Ko Kurshi Pe Baitha Gaye’ (My grandfather has made the constitution. Untouchables who were prohibited from sitting on the land have now been empowered to sit on the chair).

Different versions of the song are very popular and still sung in Awadh and Eastern Uttar Pradesh at marriage ceremonies of Dalit communities. The loud recitation of such songs praising the constitution and their public broadcasting through loudspeakers compels the people to know about the constitution.

The Constitution in the Urdu Public Sphere

The advocacy of the Indian Constitution in terms of its provision for minority rights through secularism, socialism, and democracy is also to be found in the Urdu public sphere. This can be seen in the nijamats of Anwar Jalalpuri in Urdu mushairas, recollecting memories of his grandfather. He had abandoned his plan to migrate to Pakistan during Partition after learning that the Indian constitution had provisions of secularism, socialism, and democracy to protect minorities. In the 1990s, the recitation of such stories became common in Urdu mushairas.

Constitutional knowledge the aspirant Middle Class

There is a huge craze for government jobs in India. To apply for these, one needs to prepare for a competitive examination. While travelling in different cities of Uttar Pradesh around 2010, I found that two books on the constitution- Our Constitution by Subhash Kashyap and The Introduction to the Constitution of India by DD Basu were quite popular. The former was published by the Government of India publication, National Book Trust, and its copies were supplied cheaply to schools. It was a commentary on the Indian constitution, and I had an opportunity to read it in 2003 when I was in the 7th class. Basu’s book presented the bare text of the Constitution, accompanied by judicial interpretations. These were the books that shaped the knowledge about the Constitution of a large number of students aspiring for jobs in government service. The period after -2010 saw the growing popularity of M. Laxmikant’s Indian Polity. Granville Austin’s Indian Constitution- The Cornerstone of the Nation stands apart, but it was still referred to as an academic text.

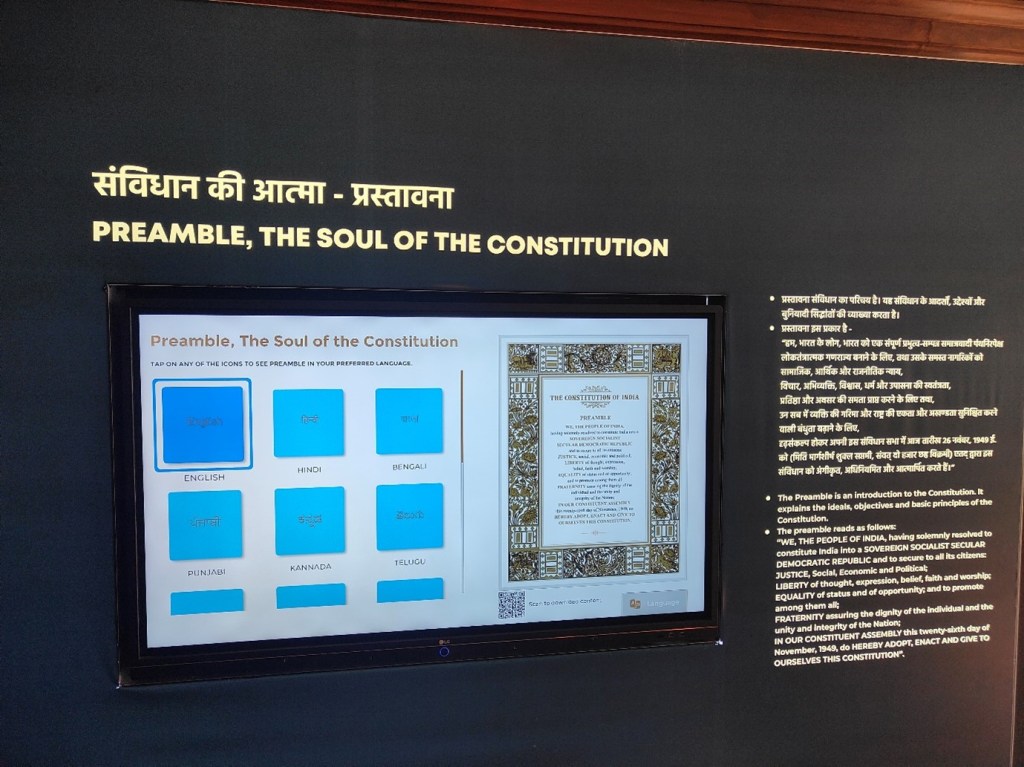

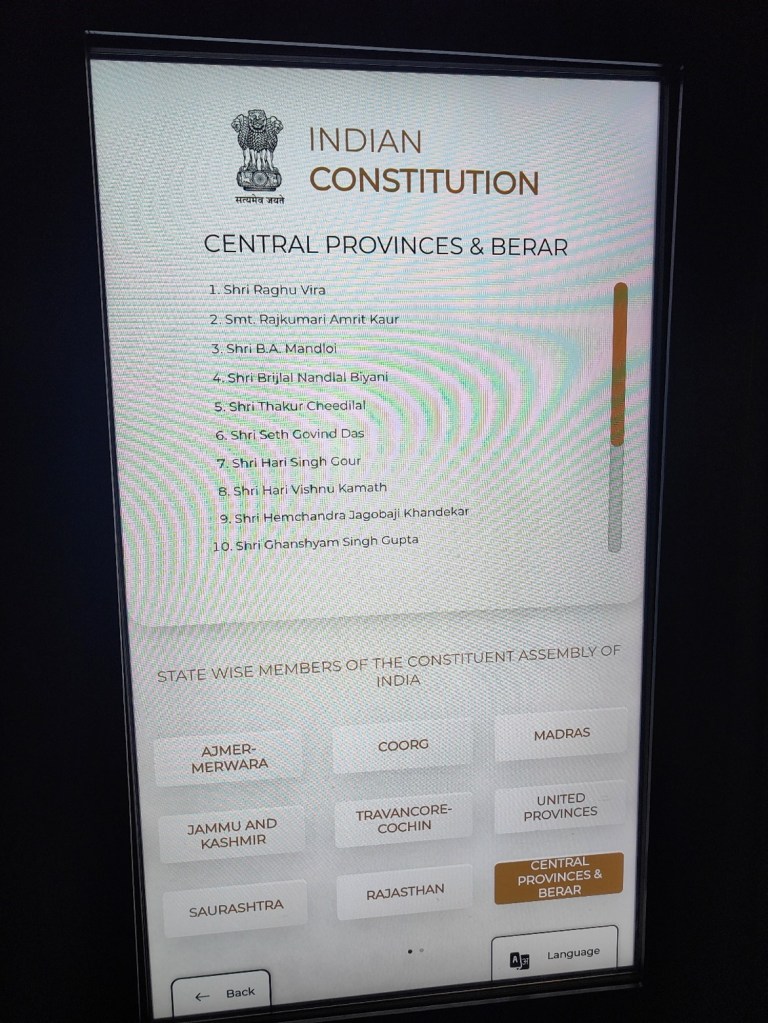

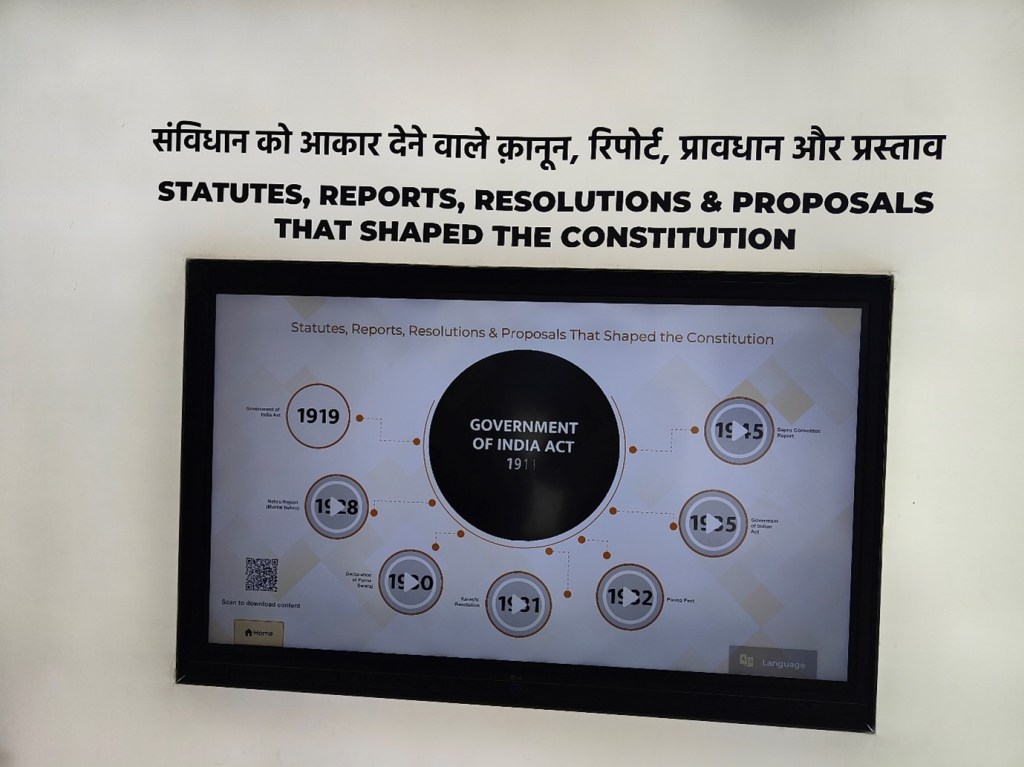

Digitalisation and Rediscovering the Meaning of the Constitution

While the Constitution of India has become popular among the middle classes, its understandings have been largely shaped by judicial interpretations of the articles. Today, however, digitalisation projects such as the ConstitutionofIndia.Net have brought a paradigm shift in the recovery of the meanings of the constitution by students and ordinary citizens. Each article of the Constitution is linked to the corresponding debates in the Constituent Assembly, which helps us understand how different versions of each article evolved. This is now becoming a popular method to understand the meanings of the articles of the Constitution, rather than through judicial interpretations alone. Digitization projects such as constitutionofindia.net and PACT have the potential to make the Constitution into a subject of mass understanding and engagement, rather than an elite project limited to judicial interpretation.

Samvidhan Yatra: The Constitution on the Move

The Mazdoor Kishan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS), which has played a very significant role in the enactment of the Right to Information Act (RTI) and the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA), took a very significant step to spread awareness about constitutional values through organising Samvidhan Yatras. Between November 26 and January 26,the Yatra covered over 50 villages of central Rajasthan: Thana, Barar, Jawaja, and Chhapli in three phases, establishing at its conclusion Samvidhan Kendra, a library, study centre, and a place to address grievances. Samvidhan Yatras provide a model for celebrating the Constitution in rural non-English speaking areas, not as a icon to be worshiped, but as a document of people’s rights, justice, and empowerment, that can serve the promotion of participatory democracy and enable structural changes at the grassroots level.

In summing up, although the Indian constitution was drafted by indirectly elected elites and representatives of princely states, its liberatory potential has made it a public document. It has been reaching the masses since its inception and no longer remains an elite document.

Dr. Kumar is an Associate Fellow at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London, and a Visiting Lecturer in Political Sociology, University of Hertfordshire, United Kingdom.